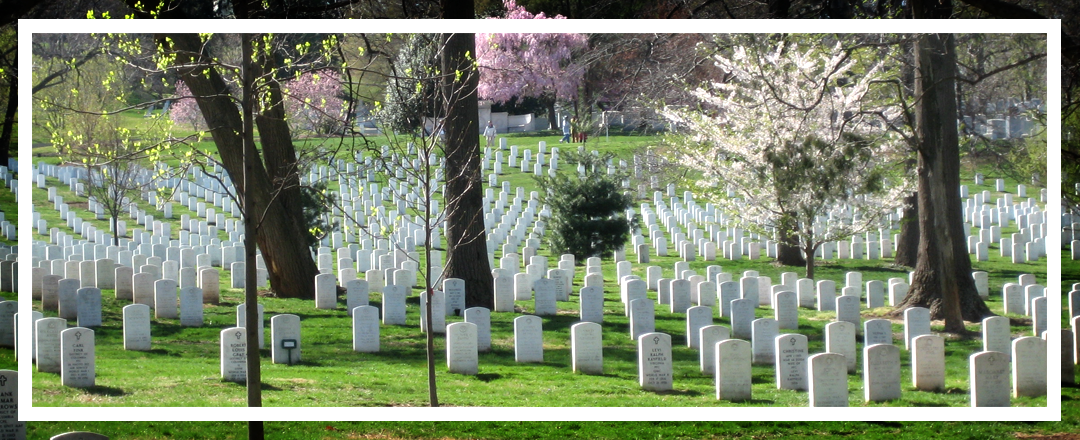

Cemeteries, war memorials, and battlefield site visits can make for invaluable teaching moments. It’s important, though, that they’re done right. To make the most of the trip, a little bit of pre-planning will go a long way.

That’s why we’ve asked social studies teacher and memorial traveller Lorelea to share her tips. Loralea teaches in Yellowknife, NT. She has led hundreds of students and adults on Explorica tours of European battlefields, and has experienced firsthand the importance of preparing students for these trips in order to maximize their impact.

Read on for her keys to making a war memorial or cemetery visit more meaningful for your students.

- Explain why you’re going

Explain to your students before you go (definitely before you get off the bus at the site) why you’re including that stop and the significance of it.

If you’re not sure yourself, either look it up and tell the kids or have the kids look it up and share the information with the group.

Stopping at a random cemetery or memorial without some background on it means students are less likely to engage (so then why are you really stopping?) and may result in behaviours that are disrespectful.

2. Teach cemetery etiquette

Explain the basic rules of etiquette for these types of visits, and expect adults and students alike to follow them. These include:

- Be respectful of other people on site. This includes not yelling, running, or making phone calls at the site.

- Feel free to wander around cemeteries and memorials. In a cemetery, move from one row to another by going to the end of the row rather than stepping between the headstones.

- It is fine to sit on steps of memorials, and to touch statues in an appropriate manner. Do not sit on the walls of the Vimy Memorial where the names of the Canadians who died and have no known grave are written.

- Feel free to eat in designated locations on site. Eating on memorials, on the grass at memorials, or in cemeteries is disrespectful.

- Do not dress up, play soldier or do war re-enactments at memorial sites: what happened there was real.

- Pay attention to and respect the ropes and signs that designate areas that are unsafe to walk in. If you find anything that looks like weaponry of any kind, do not disturb it: shells can still detonate even after all this time.

- Feel free to leave commemorative items (flowers, miniature flags, plaques, wreaths, photos, personal keepsakes, crosses, written tributes, etc.) at the sites. Do not take any of these, or anything else, away from the site.

- Be respectful of the space and what – and whom – it stands for: pick up after yourselves, do not damage the site, and shut the gate when you leave.

3. Assign pre-trip research

Having students research a soldier buried in a cemetery you are going to be visiting is a very effective way of engaging them in the site and the reason for the stop. This can be done ahead of time as a research project, or you can have them find a soldier when they arrive on site.

Every Commonwealth cemetery or memorial with names of the fallen inscribed on it contains a book that lists the soldiers buried in the cemetery, their grave reference numbers, and a map of the cemetery. These can be found in the cemetery register box, which is usually located in a wall near the entrance to the cemetery.

Are you interested in taking your students abroad for a history tour? Check out our Canadian History tour collection.